Communicating with Aliens

I’ve been communicating with aliens since my early teens. It’s a challenging way to conduct a relationship – when not only do you speak a different language, but you also see and interact with the world in entirely different ways. To breach the barrier between yourself and a genuine alien requires thought, effort, frustration, and a constant awareness of the limitations of making such a connection. But when it works – when you find even some small arena of shared experience and connection – the results can be extremely satisfying.

I don’t mean talking to Martians, or beings from another planet or solar system or galaxy. I don’t mean I believe aliens have abducted me, as the poor victims of irresponsible hypnosis “therapies” and implanted memories famously did in the 1990s.

I mean that for much of my life I have attempted to communicate with species other than our own. That is, with non-human species. Specifically: with wild animals.

***

I’m a Star Trek guy, not a Star Wars guy. For me, Star Trek was engaging and inspiring, as well as thought provoking, because of its fundamental embrace of rationality, humanistic values, and the future of liberal (lower case “L”) society over ancient tribalistic mythologies and Seventies new age spirituality.

But I confess that the one thing that always amused me about Star Trek is that for all its apparent interest in seeking out and communicating with alien species, the alien always turned out to be a human with some crap glued to its head.

Now, this trait was not unique to Start Trek. Almost universally, stories of science fiction and space travel invariably lead to meeting up with beings that look and act like humans; seen “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” lately? The notable and constant exceptions of course are when the aliens are monsters, determined from the outset to destroy us. “Alien” and “Aliens” are aptly named, but the same goes for Godzilla. Etcetera.

So while we pretend to desire and imagine communicating with other species, by and large we don’t act on it. Instead, we communicate with other pseudo-humans. Partly this is from our own obsession with our homocentric vision of the universe of living beings. And partly it stems from a simple lack of imagination.

There are exceptions, of course. “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” makes an attempt to envision such an encounter, far different from that portrayed in “E.T.” which is basically a rewrite that, if you replaced the rubber puppet with a dog, could have been entitled “A Boy and His Dog.” Just substitute “Lassie, Go Home” for

“E.T. phone home.”

Even better conceived is the 2015 film, “Arrival,” and its lingering sense of inescapable mystery in a story about a linguist trying to learn to communicate with aliens of a species dramatically different from humans.

There was a single and very notable episode of Star Trek entitled “Devil in the Dark” that did attempt to forge the sizable gap between humans and a significantly alien species. This was about the crew of the Enterprise making contact with a silicon-based life form called The Horta, which eventually, after a mind meld with Spock, constructs a profoundly affecting message: “No kill I.” In a memoir years later, William Shatner declared this episode to be his favorite of the original series. It’s one of mine as well.

And yet, for all of our imaginary searching of the cosmos for an alien species to communicate with, some people have the genuine opportunity to do so right here on earth, namely those who have contact with wild animals.

*

By this, I do not mean in the cartoony Dr. Doolitle kind of way. And neither do I mean communicating with domestic animal pets, which have already been significantly altered over tens of thousands of years in order to be able to detect certain human communication, particularly regarding emotional state, and to adapt to humans as companions. Certainly those relationships can be rewarding. But it’s different with a wild animal.

A wild animal has what I might dub a sense of its own independent being, for lack of a better description, that differs from that of a domesticated animal. Dogs have been deliberately bred to retain neotenic features and behaviors – maintaining juvenile characteristics into adulthood and throughout their adult lives. A dog, like a child, feels happier and more secure if it is being told what to do, and can successfully fulfill such commands and garner the satisfying pleasures of the rewards. Dogs have been selectively bred to be permanent children.

Wild animals are different. Even a small mammal – a squirrel, for instance – is far more readily tamable than it is trainable. Yes, some wild animals can be trained, much in the manner of circus animals, but taming and training are two different things. You might have a perfectly tame relationship with that wild squirrel, but in the absence of excessive and constant focus on operant conditioning, behavior modification and positive reinforcement, that squirrel will not be particularly inclined to obey commands that your dog would gladly respond to in an instant, even without an immediate reward. That sense of independence I mentioned doesn’t mean the animal is self-aware. But it means that the animal acts independently in the world, and it would be unnatural for it to accept commands for the sake of it. A wild animal may know and readily recognize its name, and look up at you when you call it, but if you follow it with a demand to “Come here” or “Don’t chew that,” the animal will be as mystified and uncaring as if you called to a perfect stranger on the street: “Hey, you. Come here.”

***

When I was a boy of about ten years of age, I was passionately interested in wildlife, and I joined a kid’s group run by the ASPCA in Manhattan. I was too shy and introverted to keep up with the program for long, but for the weeks that I attended, my overwhelming thrill was my first opportunities to engage firsthand with wild animals, notably in this case, coati mundi, the long-snouted South American member of the raccoon family. There was a kinkajou on hand as well, and thus began my lifelong attempts to engage with wildlife.

At about age 15 I became deeply interested in saltwater (coral reef) aquariums, a mysteriously difficult and little known aspect of the aquarium hobby at the time, and then at 16 I brought home my first snake, a Florida Chain Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula floridana), because I was old enough and determined enough to do so over my mother’s objections. Thanks to my obsessive nature as a student researcher, by the time I was 17 I was hired by one of the three largest saltwater-focused aquarium stores in New York City, and within a year identified in a specialty hobbyist magazine as one of the leading experts in the country. As I continued my career in the retail pet and aquarium industry over the ensuing decade, I would write about marine aquaria and reptile husbandry for a number of national magazines, both within the trade and for the public, while keeping and in fact breeding snakes at home. At the same time I also became a wildlife advocate and educator, working a part-time wolf handler for a grass roots wolf conservation group; and a rescuer of failed wild animal pets, leading to a household filled with abandoned dogs, cats, ferrets and even much wilder species, along with a sizable collection of snakes.

Let me be clear here: I don’t believe in keeping wild mammalian pets. We have spent tends of thousands of years customizing dogs and cats in order to make them tractable and adaptable to human companionship – in other words, turning them into domestic animals – and yet we kill millions of such animals every year because people fail to successfully and properly keep them. Hence wild animals, which lack the domesticity bred into our pet species, are invariably doomed to do far worse. All of the wild animals I ever lived with were rescues because of someone else’s failures. People buy baby wild animals in states where it is sadly legal and unchecked because the animals are cute and they are assured that if you raise them yourself they will turn into pets. Then they turn into adults that are independent, stubborn, smelly, and not interested in our expected rules for pets. And then these animals are given up, and most are destroyed because zoos do not want socialized animals that are somewhere between wild and tamed. Or they end up in the worst possible zoos that are roadside attractions rather than educational and scientific institutions.

It was in that context that I occasionally would rescue an animal – someone else’s terrible mistake and failure – rather than see it destroyed. It made life difficult and challenging and at one point I didn’t leave my home for more than 60 hours over a period of 12 years, because of the animals that lived with me as my guests – not as “pets” but as respected co-inhabitants.

I don’t recommend it.

But … the one upside of that experience, and of being a wolf handler, was the opportunity to communicate with aliens.

The only way to have a meaningful and productive relationship with a wolf, or an otter, or a giant python — all experiences I have had — or (when I was a keeper at the New York Aquarium) when hand feeding a giant Pacific octopus or helping to relocate a Beluga whale — is to abandon our preconceptions about pets, and our toxic and ignorant prejudices about man “having dominion” over animals, and start from scratch with the assumption that the other animal is its own being, that must be treated with respect, rather than with demands. And then you begin to try to figure out, with great effort, how to find some small bit of common ground between you.

When it works, it can be quite wondrous, and at moments perhaps even awe-inspiring. But it’s not easy, it is filled with challenges, and it is not for everyone. Wild animals are a far cry of difference from domestic animals. Roy Horn, of the legendary magician duo Siegfried and Roy, was as fine a wild animal keeper and handler as can possibly be imagined. One night one of his most reliable tigers attacked him, ever so briefly, and in mere seconds, the career of Siegfried and Roy was ended forever.

Wild animals, no matter how apparently tame, or possibly trained, are not and never will be domestic animals. Don’t keep them as pets. But if you have the chance to communicate with one, even once, it can be an unforgettable experience. While I eventually elected to leave the pet industry, because its relationship with animals is highly exploitive and purely commercial, I still value those experiences immensely, and am always thrilled at the opportunity to get a little closer to a wild animal, perhaps at a zoo or aquarium, even if only for a few moments. These moments are – and should be – genuinely humbling. Because to recognize the being within that alien is to recognize that our vaunted uniqueness is at best a matter of degree, not kind. We may find it difficult to communicate with aliens, but to the extent that we can, we are inescapably discovering our similarities more than our differences.

And that is my longish answer to the question: Why keep snakes?

*

After all, what could be more alien to the human experience than to have no limbs, and yet be able to move over large natural territories? What could be more alien than needing to obtain food by capturing live animals, yet without limbs or claws to grasp or run with? What could be more alien than to periodically go temporarily blind and need to hide out in safety, until after a week or more, one’s entire skin sheds as a whole, presenting a new skin to the world?

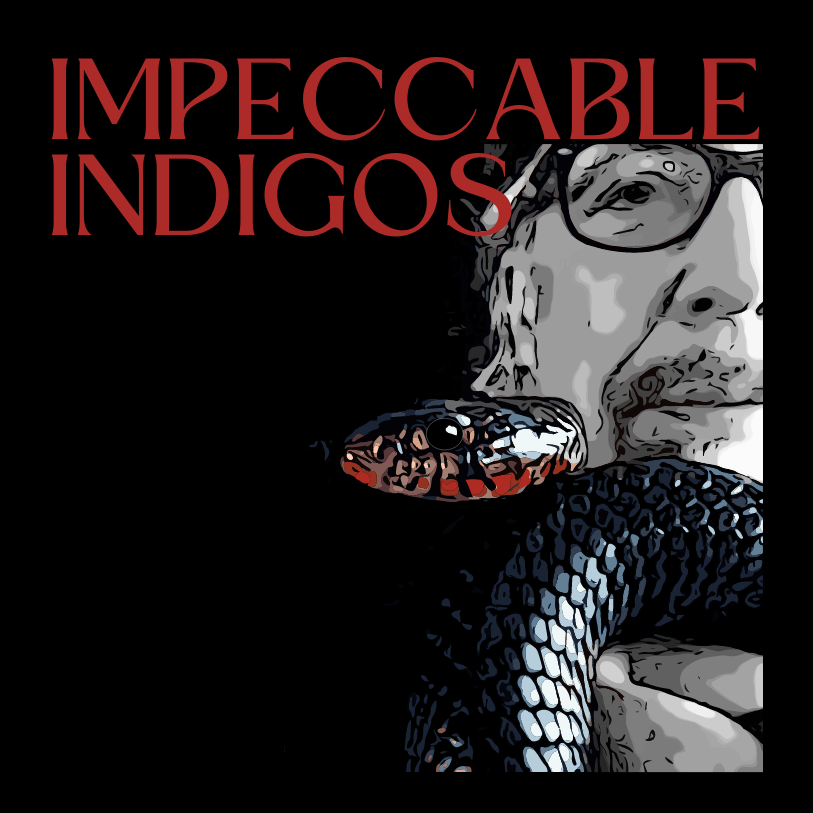

The more one handles snakes the more remarkable they seem to me. After more than half a century since my first, I remain ever amazed at their versatility, their beauty, their behavior, and oftentimes their intelligence (which is why I specialize in Eastern Indigo Snakes, among a small handful of the most intelligent and interactive of all snake species).

It is never a perfect conversation. It is adaptive, educational, and requires imagination and learning on a constant basis.

But there are few human experiences as unique as communicating with aliens – an experience that can be far more challenging, and interesting, than communicating with another human with some crap on its head.

One needn’t leave the solar system, or even the earth’s own atmosphere. I keep snakes in order to have the experience of communicating with aliens.

***