My Story

Greetings. I’m Jamy Ian Swiss.

In real life, I’m a professional magician, speaker, and writer, the author of six books and countless articles, reviews and other writings.

You can find out about my work at JamyIanSwiss.com.

But that’s all I’m going to say about that here at Impeccable Indigos. From here on in, we’re here to talk about Eastern Indigo snakes!

I’m Jamy Ian Swiss. I brought home my first snake — a Florida Chain Kingsnake — when I was 16 years old.

I began working in the retail pet and aquarium industry when I was 17, and specialized in marine aquaria, and snakes and other reptiles.

I published articles about marine aqualogy and reptile husbandry in national magazines, in both trade journals and for the public.

I’ve been a wildlife activist, a wolf handler, a keeper at the New York Aquarium, and an educator and handler at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Insect Zoo.

I bred my first pair of Eastern Indigo Snakes in 1974. I successfully hatched the entire clutch of 11 eggs.

I quit the pet industry after a decade and did not keep animals again for the ensuing three decades.

In July 2017 I attended a reptile show and encountered Indigo Snakes again.

In August of 2021 I brought home a young female Eastern Indigo.

I am currently raising a small, select (2.3) future breeding colony of Eastern Indigo Snakes

a day in a previous life

I had several careers before I elected to change my lifelong magic hobby to my job when I was 29 years old. From the age of 17, I spent about a decade in the pet and aquarium business, working in and managing salt water aquarium departments, and eventually running an entire neighborhood retail store. My interest stemmed from a lifelong interest in wildlife. By the time I was in my late teens I began to get some local and national recognition as a salt water aquarium expert, and I wrote for national industry magazines, including a year-long series on that subject, and then a half-year series on snakes and reptiles. And as a hobbyist, in the 1970s I bred snakes at home, including Boa Constrictors, and … Eastern Indigo Snakes.

[PHOTO: July 8, 2017 — Robert Bruce adult Indigo]

“And as a hobbyist, in the 1970s I bred snakes at home, including Boa Constrictors, and …

… Eastern Indigo Snakes.”

At the same time I was also a wildlife activist, serving as a wolf handler and lecturer, and rescuing failed mammalian wild animal pets (which is invariably the outcome of such purchases). I lived in a household of wild and domestic animal rescues, along with the snakes and salt water tanks. A couple of my most profoundly important personal relationships grew out of shared animal collecting and activism interests. I wrote a column for Pet News magazine for about a year. When I was 23, I was interviewed three times to be considered for the first Curator of Education at the Staten Island Zoo—and that would have made for a very different life. And when I failed to land that position (I should have cut my hair), I walked away from the pet industry, which is not a comfortable place for people who care about animals and wildlife. After that I worked one day a week for a year as a keeper at the Coney Island Aquarium. In sum, animals were a defining part of my life for many years.

Once I changed careers, however, show business was not conducive to big apartments nor to being tied down to animal care. By the time I moved to the Washington D.C. area in the 1980s, most of the animals were gone and the last couple died of old age in my first years there. For a time I would end up working in the National Museum of Natural History as a docent in the Insect Zoo, doing tarantula demonstrations and the like. But that was my last involvement with animals, and once I left the industry, I never kept animals again for the next four decades. My interest and expertise remained stored as huge locked boxes in my brain. Occasionally some circumstance or other—a backstage tour of a zoo or aquarium, perhaps—would serve to dial the combination to the vault, and trigger the door to open for a little while and I would get to poke through some of the contents. I'm still someone who will do anything for a backstage tour at a zoo or aquarium, a wild animal preserve or a wolf sanctuary, when the opportunity arises. But other than that, animals were in my past, with few reminders around me except for some photos on the walls of me with wolves I have known.

On July 9, 2017, I attended a big reptile show in San Diego, the first time I had been around reptiles in more years than I could recall. I don't remember the last time I had such an enjoyably self indulgent (in a good way), immersive day. There was plenty to look at, and I had the chance to get a few lovely animals in my hands, and share my joy and passions with my partner Ann and our youngest, then seven-year-old son.

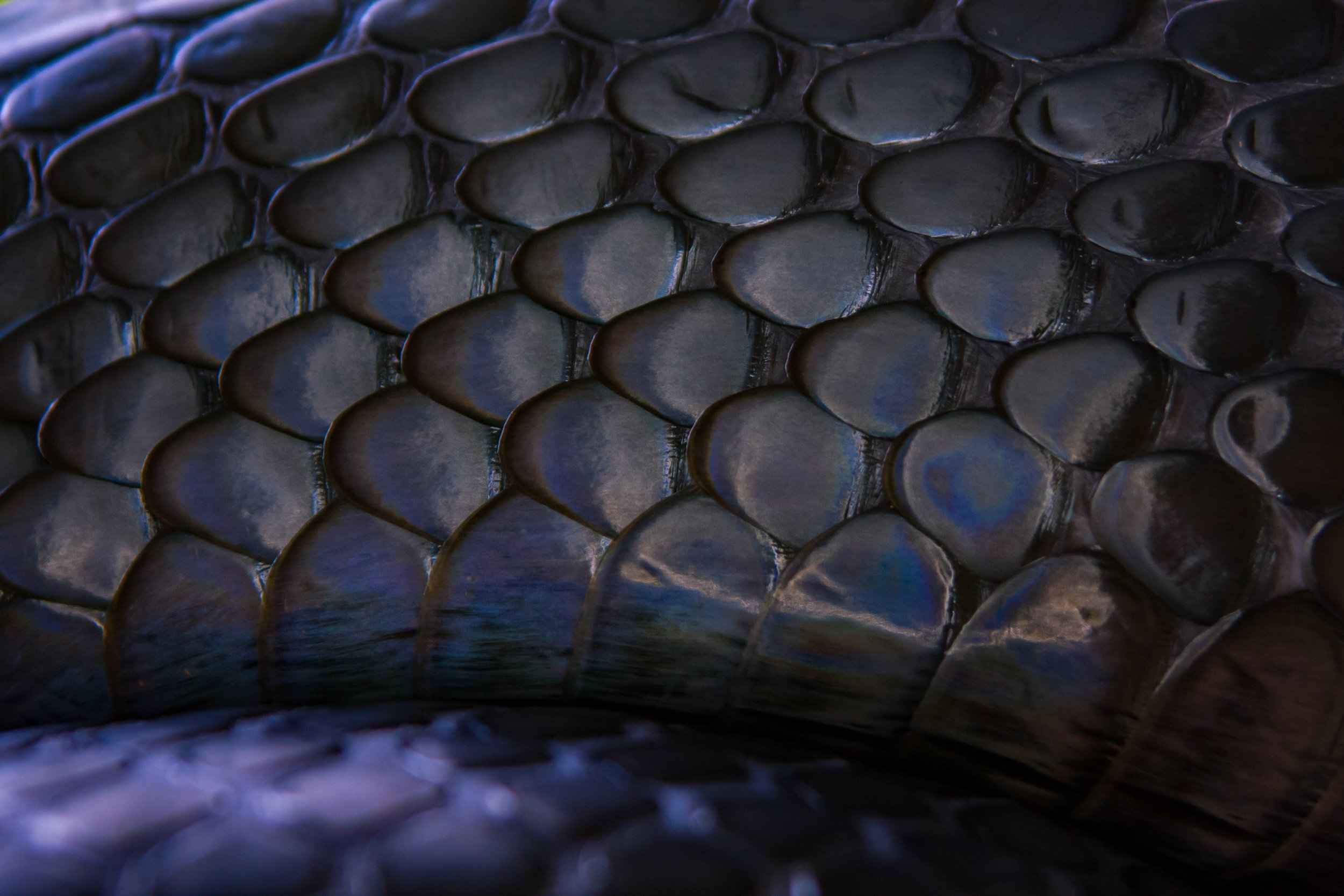

But the highlight of the day was a distant hope that became a reality. Ever since I noted the dates of the show, I had fantasized running across an Indigo Snake, my favorite species that I had successfully bred so many years ago, and the big male of the pair was the best tame reptile I ever had. Indigos have been a protected species for decades and they have been rarely available in the collector world since being put on the Federal Endangered Species List in 1978, which prohibits taking them from the wild, or even handling them if you encounter one.

After walking the show for a couple of hours I was convinced I would not see one, which was no surprise. But then I walked past a small out-of-the way booth I had somehow missed till then, and suddenly—there they were. I stopped in my tracks and gasped.

There was an adult pair out for view, the female resting in an open container and the five or six-foot male held by the man seated behind the small counter. His young adolescent daughter sat next to him, and on the counter in front of her were a couple of containers with another three juvenile specimens.

I started up a conversation with the exhibitor, briefly mentioning that I had bred the species in the 1970s, but not pressing my case any further, hoping that might pique his interest. I didn’t ask to handle the snake, since I could immediately tell that he was being extremely cautious with them. Indigos will almost never bite, but they’re a large, active snake and it takes a some experience and a little finesse to get them to settle down, otherwise they will quickly squirm away from you, because they tend to be more curious than the typical tame python or boa. So I merely touched the animal, and slowly answered the breeder's curious questions, while I made clear my particular fondness for the species.

After awhile he put the snake in my hands, but kept one hand on the tail due to concerns about show management hassling dealers about security and safety. We kept up the conversation as I asked him about his own history. I discovered that he was a one-time herpetologist (actually rather unusual among professional reptile breeders and the exhibitors at such shows) who had put aside research to specialize in exclusively breeding this rare and precious species, with a focus on maintaining genetic variety amid his breeding inventory. Most Indigo breeders fail to do this because of the snake’s rarity and expense, and hence inbreeding is a real and ever-present concern for the captive bred population. A certain degree of inbreeding is unavoidable after decades of protection and separation between the wild and captive populations, and even the small wild populations are inescapably inbred to some degree.

The snake settled into my arms like a content puppy, and after awhile, the breeder simply released him to me. We continued to speak, while we both answered questions from passersby about the glossy black beauty with a rust red chin, and I let people carefully touch the snake with the same level of care and caution the breeder had been previously exerting. (When you've had a real wolf on a leash being handled by pressing crowds of thousands of people in a day, managing a big snake safely is child's play.)

The cautious Indigo breeder understood that we shared something in our special appreciation for this distinctly beautiful and fascinating species, and eventually, very kindly, simply left his valuable reptile friend in my hands. I stood there for what easily amounted to 45 minutes with that animal comfortably resting in my arms most of the time, and I simply could not have been happier, and my day could not have been better as a result. Eventually I forced myself to hand the snake back, and bid him and his patient caretaker farewell.

The door in my head remained open for the rest of the night, as I continued to recount tales of snakes and other animal histories to Ann in the darkness, as my night wound down. The next day, that heavy door swung slowly closed, and I expected it to latch itself tight again soon thereafter. It had been fun to rifle through some of the files and drawers while I was rummaging about inside again for awhile. And oh my, what a magical animal came along with me for the visit.

But I was wrong. That day — my first the encounter with Indigos in more than thirty years — had lit a slow burning fuse that eventually blew the door off that long locked compartment. Almost exactly five years later, ImpeccableIndigos.com is making its debut, backed by a future breeding colony of young Eastern Indigo Snakes.

Taking a piece of steak.